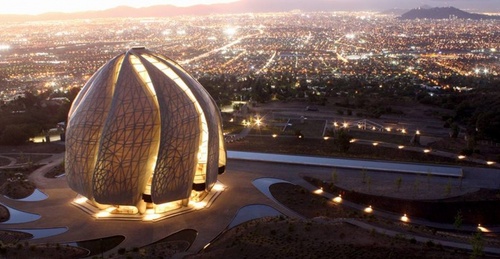

Why Do Baha’is Fast Every Year? Faraneh Hedayati•Feb 29, 2016 Verily, I say, fasting is the supreme remedy and the most great healing for the disease of self and passion. – Baha’u’llah, p. XVII, The Importance of Obligatory Prayer and…

Why Do Baha’is Fast Every Year?